It's hard to believe how much has changed since that fateful first day. When I first started I had to absorb so much stuff at my new job that I could barely keep up with it all. A part of me wishes I could go back and relive those days, just so I could see all the stuff I missed in the whirlwind of events. During my first month a lot of stuff probably changed right before my eyes without my realizing it. I'm sure I'd be amazed at how different this place was when I first started.

After a year I feel I can truly say I've experienced a different culture (more so than the "cross-cultural experience" that was required of me in college allowed me to), and while I'm nowhere close to having a complete understanding of it, I think I'm learning how to observe it thoughtfully and gain a better feel for it.

One discovery I've made since I've been here is the writing of Theodore Dalrymple. Discovering a writer might seem minor by some people's standards, but for me, it's been deeply meaningful. In my lonely, often isolated existence here, his work has been at times a source of comfort, and in addition, it's so fascinating that it often leaves me awestruck. One piece that I found particularly spellbinding was How to Read a Society, from the Spring 2000 edition of City Journal. In it, he discusses the writings of two 19th Century Frenchmen: the Marquis de Custine and Alexis de Tocqueville, who traveled and analyzed foreign cultures. Custine's analysis of Russia in 1839 was particularly interesting, and it foreshadowed the Soviet Union remarkably. Dalrymple's commentary sums it up well:

Whether describing a building or a social institution, Custine never lost sight of, for him, the key question: what was its effect upon the minds of men? For Custine, man was above all a thinking, conscious being: not even despotism could negate that. Without understanding the thoughts of the population, you could understand nothing about Russia, and its future would remain inexplicable to you.While my attempts to understand Korean society have always taken a psychological approach, this article made me think about how even seemingly trivial things can give clues. I don't feel I've made any mind-blowing discoveries, but I do feel that keeping my eyes open is helping me to make sense of what I see.

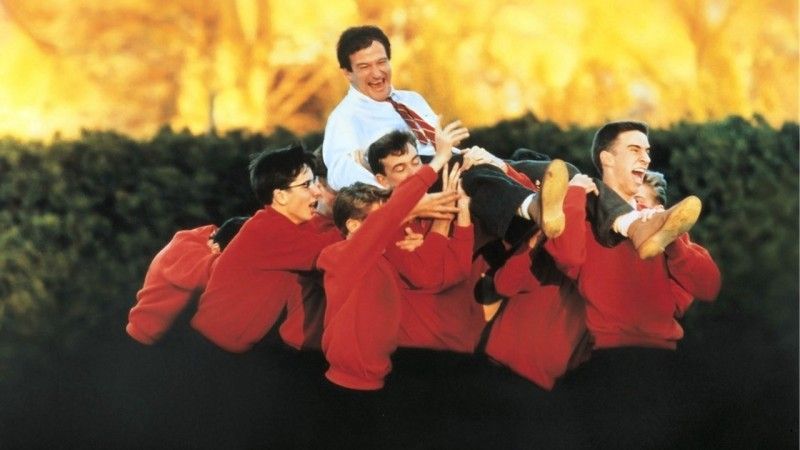

There was one thing that particularly stood out to me as an example of differing cultural outlooks, which I hadn't read about beforehand. To demonstrate, I think it might be good to first look at the movie Dead Poets Society. I'll assume my reader has seen it (because if he hasn't, he should), otherwise I'll include the standard warning of "spoilers ahead!"

Quick and dirty synopsis: The movie is about a group of boys attending a prestigious boarding school called Welton Academy, and how their lives are changed by an unconventional yet inspirational English teacher named John Keating. Several boys' stories are shown, but the one I want to focus on is Neil.

Neil, like the other boys in the group, is spurred to action by Keating's motto: Carpe diem! ("Seize the day"). When he hears about auditions for a stage production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, he decides to try out, as acting was something that had always interested him. There's only one problem: he has a strict father who doesn't approve of his son acting. He expects his son to become a doctor, and wants nothing distracting him from that goal. We learn that part of the reason for this is because Neil's father isn't a wealthy man, and he made a lot of sacrifices to send Neil to Welton. In that light, his father's actions are understandable, but we still feel bad for Neil.

Despite his father's disapproval, Neil continues ahead with the play, and when his father finds out, he's as furious as you would expect. He pulls Neil out of Welton in order to send him to military school, which leads a heartbroken Neil to commit suicide.

The message of this storyline (and really, the movie itself) is that people need to be able to follow the passions in their hearts, or they'll end up dead (either physically or internally). To a Western audience, such a message isn't terribly radical. After all, right or wrong, the values of individualism and personal happiness have become tenets of our cultural mentality. We understand why Neil's father was so tough on him, but when we see Neil's tragic fate, the message is clear: Neil should've been allowed to choose for himself what he wanted.

I'd like to contrast that with a work of fiction from Korea. Remember Spring Day? Yeah, I just reread my recap of it and I'd forgotten a lot of the things I mentioned in it. One of the plotlines in it is relevant to this discussion, so again, if you haven't seen it you're getting another spoiler warning (though truthfully, watching Spring Day shouldn't be high on anyone's priority list).

One of the characters in Spring Day is a young man named Eun-Seop. He's a doctor, but he hates his job. The only reason he became a doctor is because his father pushed him down that path. He has a passion though: jazz music. He would love to be a jazz musician, except he has that darn doctor job standing in his way.

Sounds similar to Neil's story, doesn't it? A father pushed his son to be a doctor, while his true passions were artistic in nature. When I first started watching the drama I just knew that he'd end up quitting his doctor job and finding true happiness with a syncopated rhythm. There was no doubt in my mind. After all, that was how it always went in America. If your current situation leaves you wanting, then you trade it for one that won't. It's either that or suicide ("it's such a strange strain on you..." Sorry, I had to throw in that Cheap Trick reference).

The only thing is...that wasn't how the story played out. Rather than ditching the stethoscope in favor of an upright bass, Eun-seop gradually applied himself more at his job and learned to make the best of his situation. In fact, his position as a doctor was what allowed him get the girl at the end (no, she wasn't a gold digger. Her small town needed a doctor, and he was able to fill the role).

To be fair, you can probably find Korean stories that follow the "American" pattern and vice versa, and it's possible that the writers of the drama originally intended for him to follow his jazz dreams (these dramas go through several rewrites over the course of their runs). It was surprising to me though, how the direction of the story belied my expectation.

Perhaps one factor is the high level of respect for the medical profession in Korea. Doctors are so revered here that it's possible they wouldn't want to portray the job as ultimately undesirable. It's commonly known that a high percentage of Korean-Americans become doctors or lawyers, and even in Korea many parents would love to see their kids go into those lines of work. Considering the country has only come out of poverty in the last 50 years or so, the older generations know how valuable financial security is, so they push their children into high-paying jobs like that.

Along those same lines though, I think, is perhaps a more important factor: Korea as a culture is less elevating of the individual's desires than the West. Let me illustrate.

At the kindergarten graduation ceremony last February, each kid gave an introduction saying "My name is __________ and I want to be a ___________." Three of the eight filled in the second blank with "doctor." Of course, it's more likely that their parents are the ones who want them to enter these careers, not they themselves. Two of my older students have talked about their futures as doctors as well. With one of them, he was talking about how good he was at soccer and I asked if he wanted to be a soccer player when he grew up. He said "No, my mother says I have to be a doctor."

Many Westerners might think that sounds cruel and spirit-crushing, but it almost seems as though these kids really feel like it's their destiny to follow the path their parents have set out for them. They seem resigned to it without any particular bitterness. If you're a Korean kid, your parents are going to force their will on you, and honoring it is just what you do.

This phenomenon has recently been dubbed "tiger parenting" thanks to a provocative excerpt published last year in the Wall Street Journal. The author, a Chinese-American woman named Amy Chua, discusses the parenting style she inherited from her own parents, which is common in Korea as well. It's a matter of pushing kids to be their best, and believing in them enough not to accept anything less. Some might criticize it, but it gets results, as Korea's rapid ascent can attest.

I see it myself with how my boss disciplines her two sons, and from hearing my students tell their stories. I read a journal entry from one girl where she talked about how her parents yelled at her for getting a bad score on a test. They claimed she didn't study hard enough, which made her want to cry. She also said in that entry that she hates studying with her father because he yells at her and she wants to hit him, but she can't because he's her father. I get the impression that her father is a tough man, because that girl's younger brother has suggested at various times that his father is scary.

While my native culture would side more with the Dead Poets Society view of personal autonomy, I don't think the Koreans' cultural outlook is wrong. After all, why do people have children? They want to contribute to the future. They want to know that after they're gone their genes will live on, and they hope that the great people of tomorrow will be connected to them in some way. A culture that understands that and honors it is a wise one.

In Confucian principles the concept of loyalty to family is called filial piety. That idea really resonated with me when I first read about it, because it seems to be in line with how I live my life. While perhaps I haven't always acted like it, I've always wanted to honor my parents and not be a failure in their eyes, because I can only imagine how heartbreaking it is to be the parent of a child who strays from the values he was raised with and disrespects the sacrifices that were made for him. The last thing I want to do is break my parents' hearts, and I'm always happy to know when they're proud of me. I don't know if I'll ever have children, but if I do, I hope they respect me in the same way.

Since I'm not Korean, I don't know what tiger parenting is like from an insider's perspective, and I can't really tell you what happens when the child fails to live up to expectations. I can only imagine that it's difficult for both parents and children (and most of us know about South Korea's high suicide rate, though I don't know that the rate among teens is significantly different than the U.S.'s). I am a bit concerned about one of the kindergarteners I mentioned above who expressed his desire to be a doctor. He's a really sweet kid, and really funny too, but if I'm being completely honest, I don't know if he has what it takes to be a doctor. He's always been one of the slower kids in class, though he does seem to try very hard. I think he'd make a great actor or comedian (shades of Neil again), but given the instability of show business, it's unlikely that many parents would choose that route for their child. I can only hope that if it becomes clear that he's not destined for a career as a doctor, this boy's parents will be understanding and help him find a more realistic path.

I guess a lot of what I've written here isn't about how the last year has impacted me, and more an opportunity to muse about culture. Perhaps I should wrap it up with some final thoughts.

I've spent most of my life wandering, too afraid to take any bold steps or go after opportunities. I don't know what life has in store for me, but whatever happens, I know that I can be proud of myself, because I've spent this last year doing something worthwhile that makes me feel like my existence is justified. Some people are cynical about what I do for a living, including many people who do it themselves. They think it's just an easy money job that most any minimally-qualified native English speaker could do. I don't look at it that way. I see it as an opportunity to help children have a better future, and I view that as a big responsibility.

Am I a good teacher? It depends on what you mean by "good." I think that as far as form and whatnot goes, I still need a lot of work. I'm not the best at controlling classrooms or communicating things clearly. I'll be the first to admit that my teaching is still a work in progress. If by "good" you mean dedicated and honest, then I believe I am. Even my coworkers have told me they think I have a good heart, which is certainly meaningful to me. I value my character, and while I can never be perfect, I want to strive to live the best I can. I hope that when my students sit in my class they can see that I really do care about them.

I've now spent one year doing a job that's given me tons of stress and frequent frustration. I put my heart and soul into it, and the decision was still made not to renew my contract once it expired. I've spent many moments lonely and isolated by both the country I'm a foreigner in and the differing attitudes of my fellow foreigners. On the surface it sounds like my year was ultimately a failure, but I can't see it as anything but a success. Here's to continued success in my next year.

No comments:

Post a Comment